Resonance and reverberate in ancient theatres, the study of Epidaurus, and the birthplace of drama.

In this essay, I will investigate the role of ancient Greek theatres that led to the birth of performance drama. As well as explore the different discoveries of the exceptional sound quality of the Epidaurus theatre due to the architectural design that allowed performances to be intelligible. In my investigation, I learned that it was a challenge to determine the exact number of ancient theatres, as several may not have been discovered or have not survived over time. However, Epidaurus is still standing today as it is considered one of the best-preserved ancient theatres in Greece.

The Theatre of Epidaurus is renowned for its architectural brilliance and unique qualities that contribute to its exceptional status. Qualities such as exceptional acoustics with efficient sound reflection, architectural harmony with semi-circular seating as seen in Figure 1 and a minimal stage building all integrated with nature in the lush hills of the Peloponnese.

The architect who designed the theatre of Epidaurus was Polykleitos the Younger, located on the northeastern corner of the Peloponnesus in Greece in the Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus, was constructed in the fourth century BC. This theatre is famous for its exceptional acoustics, Polykleitos’s achievement is still considered a masterpiece many thousand years after. Actors on stage can be perfectly heard by all 14,000 spectators, regardless of their seating.

The acoustics of Epidaurus are closely tied to the historical context of ancient Greece and investigating the acoustic properties provides insights into the role of theatres in ancient Greek society, including their use in religious rituals, civic events, and dramatical performances. Greek theatres were primarily designed for the performance of tragedies, comedies, and other dramatic plays during religious festivals. The focus was on storytelling and dramatic performances. Kuritz (1988, page 2) states theatres to have started at the beginning of civilisation with religious rituals. It was a way to for the community elders to communicate with the supernatural. With progression theatres started to adopt dramatic acts which was a rarity spread west from Greece, this was encouraged to gain an individual expression of the appearance of drama within the context of religious celebration. “Of all people, the Greeks have best dreamed the dream of life.” The words by Goethe, which illustrates how ancient Greece was seen in History. Phenomenal! Greece was made up of three main independent centres and in the following order is how theatres developed: Ionia, Sparta, and Athens. By the time it reached Athens, they gathered the best qualities of the others and reached a point where they became the dominant culture in the fifth century B.C. The best qualities insisted of Ionia’s single actor and Sparta’s group acts, which in turn gave birth to the dramatic theatre.

Actors wore masks during their dramatical plays to provide exaggerated expressions and allow the audience to distinguish between actors from a distance. They started to be implemented in the time of Aeschylus in the sixth century AD. In the research conducted by Varakis (2004), one of the actors stated that the volume of their voice had increased by the mask during the performance. Most of the evidence comes from vase paintings and figures as shown in Figure 2 which depict actors preparing for a play. The mask shows the exaggeration with the gaping mouth and knitted brows. No physical masks survived to be displayed now, it is believed to be due to the organic material the masks were made from.

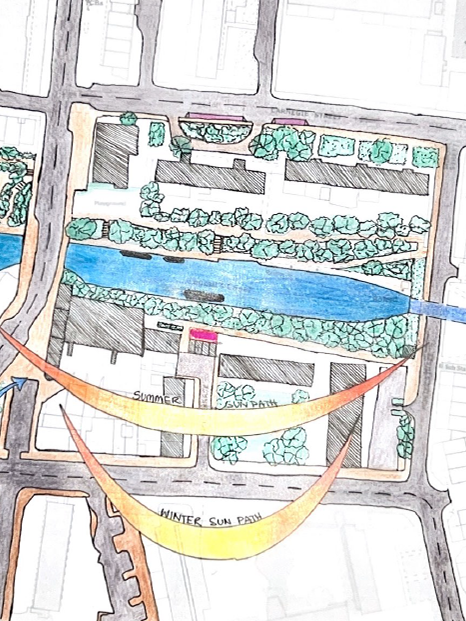

Greek theatres were built into natural slopes and hillsides to provide a natural Amphitheatre shape. The curved fan shape allows for an even distribution of sound evenly through reverberation. The seats at Epidaurus are made up of a corrugated surface which acts as acoustic filters by noticing the resonance of the theatre rather than the surrounding sound of the landscape. The limestone and Poros stone seating called the auditorium or Koilon, were semicircular and divided into sections by stairways. Mentioned by Zikakou (2023) in a recent article that this material is known to be sound reflecting that produces an echo. The orchestra, where the chorus performed, is the circular area in front of the stage, as shown in Figure 3. The stage, or skene, in Greek theatres, was a simple structure at the back of the orchestra and was primarily used as a backdrop for performances.

Architects and builders managed to create spaces with excellent acoustics without the aid of modern technology can be a testament to their skill and ingenuity. The acoustics of ancient Greek theatres, including Epidaurus, showcase the remarkable architectural and engineering skills of the time. It is startling, on the other hand, that Greek builders probably did not understand what led to this because the misunderstanding about the role of the limestone seats possibly shielded from duplicating its effect on other theatres built after. Experts both on acoustics and engineering were brought together to discuss all their findings on ancient theatres at the International Congress, which took place at the University of Patras. They focused on three conditions sound transported by the wind, the rhythm of speech, and the sound created by the actors by their masks. However, Izenour (1996) stated that the reason for the exceptional quality of sound is the large space between the audience and the actors. In addition, Psarras, other acoustic engineers, and acoustic researchers (2013) shared a great deal of work on the Epidaurus and confirm high-speed travel in space as Izenour stated as well as the lack of effect on the resonance found on the environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and wind. Instead, the presence of the audience is what creates the consistency in actors’ intelligibility.

As mentioned above, it is known that the acoustics of ancient theatres are a subject of scientific interest. Studying how sound behaved in these spaces can involve acousticians and researchers who seek to understand the physics of sound propagation in different architectural settings. Methods used by researchers to study ancient acoustics and their findings are the following but not limited to computer modelling and simulation, field experiments, 3D laser scanning and material analysis. An example is shown in the research with Lokki and his team (2013), using a 3D model of the Koilon at the Epidaurus theatre to measure the difference between frequencies for both the model and at the theatre. The results show that to achieve high intelligibility of actors’ voices, a high signal-to-noise ratio is required. Epidaurus is located at the countryside which is peaceful and in turn the low noise allows for a high signal to noise ratio. This would have been more evident when the stage was at its full form, proving a noise barrier from the valley as shown in Figure 4.

Other acoustic simulations used to test in open air theatres were ODEON and CATT-Acoustics, which is making a 3D model to make a stimulation of acoustics and display them in different ways. However, CATT-Acoustics has been deemed a more appropriate way of measuring the open-air theatre model. The limitations faced, is that Epidaurus theatre is unroofed.

Other acoustic simulations used to test in open air theatres were ODEON and CATT-Acoustics, which is making a 3D model to make a stimulation of acoustics and display them in different ways. However, CATT-Acoustics has been deemed a more appropriate way of measuring the open-air theatre model. The limitations faced, is that Epidaurus theatre is unroofed.

The acoustics of theatres had a direct impact on the quality of theatrical performances. Exploring how sound travelled in these spaces can provide a deeper understanding of how the ancient Greeks approached drama, music, and other performances, allowing the audience to hear even quiet sounds from the stage. This has been proven by all the visitors such as Menta (2017). He shared during a performance of Helen at his visit to the theatre of Epidaurus ‘despite the lack of any microphones, I heard every word.’ He explained that the feeling of attending the performance was overwhelming and really focused on hearing the play, rather than seeing the play. There is not a clear divide between the audience as you would see in modern theatre, all people are sat on this one continues stage, listening to the same act. It is astonishing! It is a monumental space which can still be enjoyed thousands of years later both by the local and a tourist attraction.

On the other hand, Hank (2017) and other Dutch researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology investigated the acoustics of three ancient theatres, including Theatre of Epidaurus. Opposing the common claims, their study, based on over 10,000 measurements, revealed that while loud speech is intelligible throughout the theatre. However, some sounds only travel halfway through the theatre, subtle sounds such as tearing paper or a whisper. The study challenges popular examples from travel guides, such as the clarity of a falling coin or a striking match. The researchers concluded that, while the theatres have good acoustic quality, it is not as exceptional as often believed, using a new measuring method to address equipment delay distortions they developed on their own.

The Roman architect Vitruvius (1960) described four distinct types of sound reflection in his book about acoustics of theatres, which one of those is ‘circumsonant’. This means also means echo, illustrating that it is inevitable that all performances produce a resonance. Similarity, in an article by Shankland (1973) he stated that due to the reflected sound which then scatters around by both the seats and the people make ‘Greek Theatres unattractive for orchestral music’.

What we find in modern theatres compared to ancient Greek theatres like Epidaurus are that they are roofed to control all environmental factors. While ancient Greek theatres like Epidaurus hold historical and cultural significance, modern theatres have embraced technological and design innovations to enhance the overall theatrical experience and meet the diverse needs of

contemporary audiences and performers. Simultaneously, Singh (2023) published that the overall architectural look of the theatres now has not changed much from their ancient look, the reason being that it is most effective. One clear difference is that the fan chape of Epidaurus is now more of a semi-circle, something like the Roman Style.

contemporary audiences and performers. Simultaneously, Singh (2023) published that the overall architectural look of the theatres now has not changed much from their ancient look, the reason being that it is most effective. One clear difference is that the fan chape of Epidaurus is now more of a semi-circle, something like the Roman Style.

In conclusion, the exploration of resonance, reverberation, and echo in ancient Greek theatres, with a focus on the renowned theatre of Epidaurus, provides valuable insights into the birthplace of performance drama. The exceptional acoustic quality of Epidaurus, credited to its architectural brilliance and integration with nature. Despite lacking modern technology, their achievements showcased a deep understanding of sound propagation, contributing to the success. Its features, including the fan shaped seating made from limestone and Poros stone contributed to its unique reverberation and echo created from the performances. The theatres were initially associated with religious rituals and evolved into spaces for dramatic performances during festivals.

The uncovering of acoustics in ancient theatre involved a combination of scientific methods. Some researchers challenge popular claims about its acoustics. While loud speech remains intelligible throughout the theatre, subtle sounds like tearing paper or a whisper are audible only up to about halfway. This nuanced understanding sheds light on the practical limitations of ancient theatres, prompting a reassessment of their perceived exceptionalism.

While the acoustics of ancient theatres continue to captivate researchers and enthusiasts alike, modern theatres have evolved to meet contemporary needs. Technological advancements, safety measures, and architectural flexibility characterize modern theatres, offering enhanced comfort, accessibility, and a broader range of performances.

In essence, the study of acoustics in ancient theatres like Epidaurus not only unveils the engineering marvels of the past but also prompts a re-evaluation of their acoustic exceptionalism. The enduring allure of these theatres, both ancient and modern, lies in their ability to transcend time, providing spaces where the magic of dramatic performances continues to resonate with audiences.

Bibliography:

Hak, Constant (2017) and other researcher from Eindhoven University of Technology, article ‘Acoustics of ancient Greek theaters found to be good, not great’.

Izenour G.C. (1996), Theater Design, 2nd ed., Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Lokki T., Southern A., Siltanen S., Savioja L. (2013), Acoustics of Epidaurus – studies with room acoustics modelling methods, Acta Acustica United with Acustica.

Menta, Ed (2017), I Finally Saw the Greek Theatres: Impressions on Teaching Undergraduate Theatre History, Journal Article, James A. B. Stone College Professor of Theatre Arts at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.

Psarras S., Hatziantoniou P., Kountouras M., Tatlas N.-A., Mourjopoulos J.N., Skarlatos D. (2013), Measurements and analysis of the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre acoustics, Journal Article.

Shankland, Robert S. (1973), Article ‘Acoustics of Greek theatres’

Singh, Karan (2023), Theatre from Ancient to Modern

Varakis, Angie (2004), Research on the ancient mask, Didaskalia - The Journal for Ancient Performance

Vitruvius (1960), Morgan, M. H., The Ten Books on Architecture, Book V, p.202.

Zikakou, Ioanna (2023), article ‘Mystery of Exceptional Sound at Greece’s Epidaurus Theater Solved’.

Izenour G.C. (1996), Theater Design, 2nd ed., Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Lokki T., Southern A., Siltanen S., Savioja L. (2013), Acoustics of Epidaurus – studies with room acoustics modelling methods, Acta Acustica United with Acustica.

Menta, Ed (2017), I Finally Saw the Greek Theatres: Impressions on Teaching Undergraduate Theatre History, Journal Article, James A. B. Stone College Professor of Theatre Arts at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.

Psarras S., Hatziantoniou P., Kountouras M., Tatlas N.-A., Mourjopoulos J.N., Skarlatos D. (2013), Measurements and analysis of the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre acoustics, Journal Article.

Shankland, Robert S. (1973), Article ‘Acoustics of Greek theatres’

Singh, Karan (2023), Theatre from Ancient to Modern

Varakis, Angie (2004), Research on the ancient mask, Didaskalia - The Journal for Ancient Performance

Vitruvius (1960), Morgan, M. H., The Ten Books on Architecture, Book V, p.202.

Zikakou, Ioanna (2023), article ‘Mystery of Exceptional Sound at Greece’s Epidaurus Theater Solved’.